Staying Fit

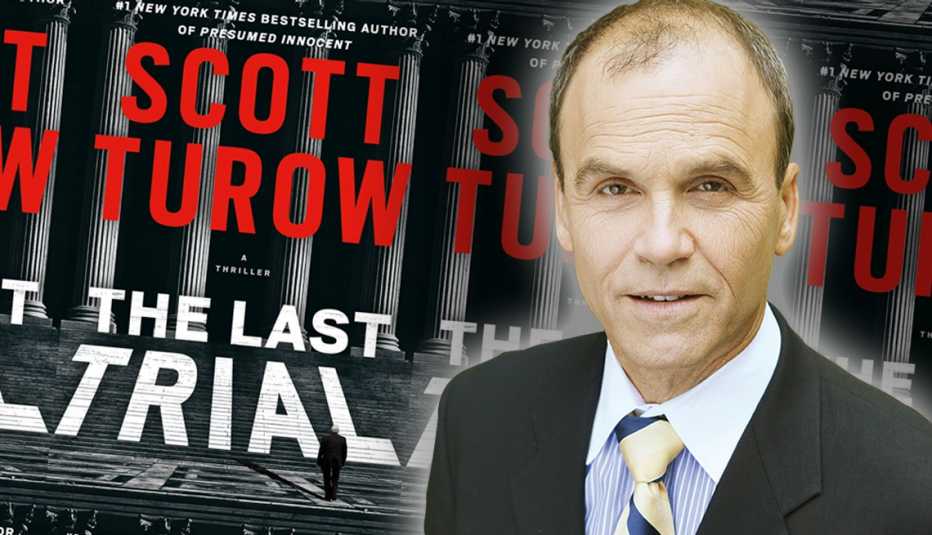

When was the last time you read a legal thriller with an 85-year-old protagonist? Check out The Last Trial. Out May 12, it's by the master of the genre, Scott Turow, 71, author of the 1987 blockbuster Presumed Innocent and other best sellers.

Full of plot twists and legal details (the author's a lawyer), The Last Trial features a Turow favorite, defense attorney Alejandro Stern, as he takes on one final case before retirement. This time, Stern is defending his longtime friend 78-year-old Dr. Kiril Pafko, an esteemed Nobel Prize–winning cancer researcher who's been accused of insider trading, fraud and murder, after the deaths of a dozen patients who took a drug he created. As Stern digs deeper into Pafko's case, he starts to wonder whether he really knew his friend.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Enjoy the dramatic prologue to Turow's whip-smart novel about aging, justice and what we owe the people we love.

Prologue

A woman screams. Shrill and desolate, the brief sound rips through the solemn hush in the corridors of the old federal courthouse.

Within the huge courtroom of the chief judge, the spectators are on their feet. The case on trial here, the criminal prosecution of a world-renowned physician, has been national news, and the gallery has been shoulder-to-shoulder every day. Now most of the onlookers are straining to see what has just happened beyond the walnut rail that bounds the area reserved for the trial participants.

The defendant's lead counsel, a very old man but still quite celebrated, has sagged from sight at the defense table. His client, the accused doctor, who is almost as aged as his attorney, kneels, holding the fallen man's limp hand by the wrist.

"No pulse,” the doctor shouts. “Help, please!"

With that, the young woman beside him, who first cried out, takes flight. She is the paralegal on the case and also the old lawyer's granddaughter, and she bulls down the center aisle of the gallery, headed toward the door. Beside the doctor, the attorney's daughter, his law partner for decades, has been largely paralyzed by distress. All along, she has approached this trial, their last case together, with foreboding. Now she is weeping spontaneously, making no sound despite the tears racing down behind her glasses. The two prosecutors, the United States Attorney and his younger assistant, have sped from their seats across the courtroom. Working together, the pair take hold of the figure heaped on the floor.

In her robe, the chief judge has rushed down from the bench, intent on taking control of the scene, but she stops, suddenly mindful that the jury remains here. Like the other onlookers, the jurors are on their feet in the box in various stricken poses. The judge points to the deputy marshal positioned near them and shouts, “Remove the jury, please,” then continues forward.

The court security officer, in his blazer and flesh-colored earpiece, has run across the courtroom to help, and with his aid, the prosecutors slowly hoist the old lawyer's body, placing him on his back on the walnut table, as his daughter shoves aside papers and equipment to make room. The old doctor quickly spreads the attorney's suit jacket and rips open his white shirt to expose his chest. The lawyer and the doctor have been friends for decades, and there is a trace of tenderness as the physician briefly presses his ear over the other man's heart, then sets the heel of his palm on the sternum of the inert figure, pumping with both hands at regular intervals.

"Someone breathe for him!” the doctor urges. The judge, who has known the lawyers on both sides for years, reacts first, pinching open the attorney's pale lips and setting her mouth on his as she exhales deeply. The sight seems to bring the daughter back to herself, and after the first dozen or so breaths, she takes over.

The prosecutors and the security officer have stepped back. Perhaps they mean to give the doctor room, or perhaps, like everyone else here, they find the sight of the old lawyer motionless on the table, like a Spartan on his shield, stark and horrifying. A small man, he has nonetheless always been a dominating presence in the courtroom. Now he lies here sadly exposed. Sparse white hairs curl across his breast, and his flesh has the grayish undertone of skim milk. The left side of his chest appears somewhat sunken where the livid mark of a surgical scar follows from just below his nipple all the way to his back. Incongruously, his red, white, and blue necktie, still knotted in his collar, hangs down his naked side.

The young woman who screamed and then fled has returned. She is an odd person. You can see that, not just because of the inch-long nail driven through her nose as decoration, but also from the slightly angry and indifferent way she deals with people. “Move, move,” she shouts, dodging up the aisle. She carries a red plastic case in her right hand, where blood is welling from her knuckles. The latch on the box in the corridor that houses the defibrillator was jammed, and after several desperate tries, the lawyer's granddaughter simply punched in the thin glass.

As she passes the front spectators’ row, one of the long line of journalists standing there remarks to a colleague beside him, “Talk about going out with your boots on."

Immediately after delivering the equipment to the doctor, the young woman wheels, pointing her bloody hand at the reporter.

"That's shit, Stew,” she says. “No way he's dying."

Excerpted from The Last Trial by Scott Turow. Copyright © 2020 by S.C.R.I.B.E., Inc. and reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Available starting May 12 at Amazon.com, Bookshop.org (where your purchase supports independent bookstores), Barnes & Noble (bn.com) and wherever else books are sold.

More From AARP

Read an Excerpt From Terry McMillan’s New Novel

You’ll fall in love with this warm, funny story by the ‘Waiting to Exhale’ author