Staying Fit

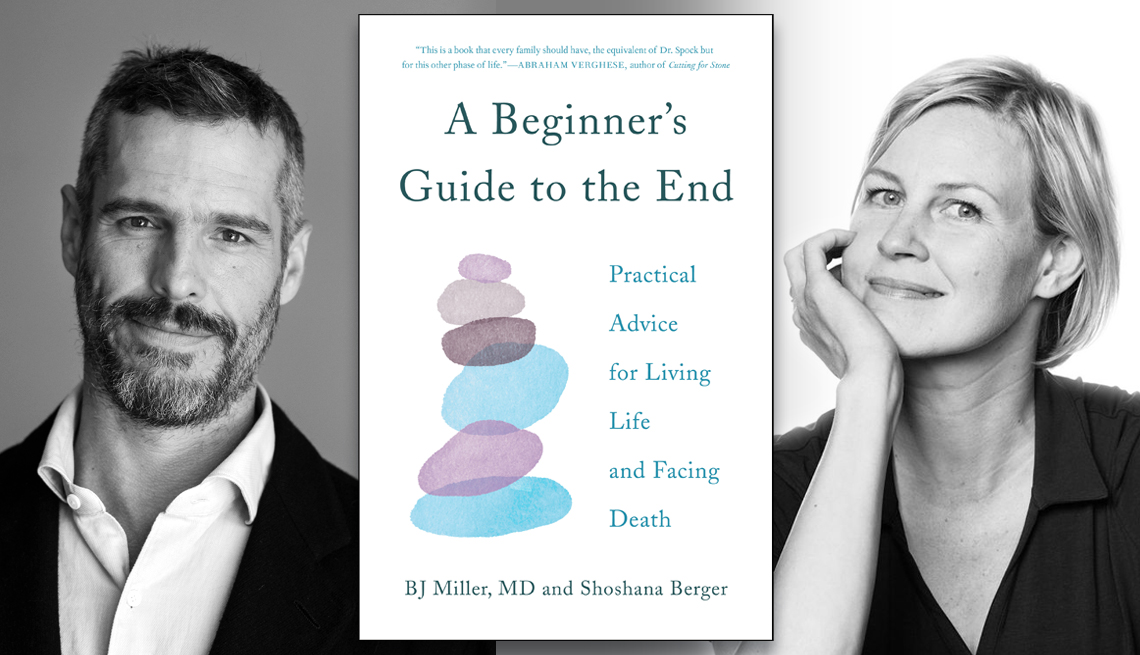

A new book designed to prepare people for death in the same way so many books prepare parents for birth hopes to reframe how death is perceived.

A Beginner's Guide to the End suggests death “can really be profound and meaningful if you feel a little bit more prepared for it, “ says coauthor Shoshana Berger.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Berger met coauthor BJ Miller, a palliative care physician, when the “wound was fresh” from the death of her father. She says Miller had a “grand vision” of how to alter the death experience.

"Death is going to come no matter what you do,” says Miller. “Try to soak that fact in. If you do, you can let it lend some urgency to your life. You can let it lend some appreciation to the time and relationships that you have.… Dying does not have to be quite so hard. In fact, it can be kind of beautiful."

The authors say one of the best gifts that a person can give to family is a conversation about end-of-life planning. They suggest discussing preferred health care choices and preferred funeral arrangements in case communication fades or a death comes unexpectedly. “All that tough stuff can be such a huge gift, and people don't really understand that.…Reframe the conversation and think of it as taking care of the people you love,” says Berger.

The book discusses the story of Ira Byock, a palliative care physician, who found a card file box on his mother's kitchen counter after she died. Inside were paperwork such as bank account numbers, transactions in progress, and her lawyer's information.

"They felt like their mother had left them a batch of freshly baked cookies on the counter. He and his sister felt like it was one last kind act as a Jewish mother leaving for her children,” says Berger.

The authors suggest leaving a “When I Die” file and putting it in a place easily discoverable by someone trusted.

It should include all accounts, logins and passwords to social media, how to access phone and computer documents, real estate deeds, and powers of attorney for finances and health care.

"The average time it takes to settle an estate is 16 months, so your family ends up with a full-time job of sleuthing through your mail and files to find all that stuff right when they are trying to figure out how to live without you,” Berger says.