AARP Hearing Center

Leonard Chayrez called his partner in a panic.

“I couldn’t remember how to use the credit card machine at the gas station, so I drove to three,” says Chayrez, a retired floral designer in Phoenix. “I kept forgetting things.”

That was in 2018. One year later, Chayrez, 58, was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, and shortly thereafter, Alzheimer’s disease. Since June 2023, he has received twice-monthly infusions of lecanemab (Leqembi), the headline-grabbing medication approved last year by the Food and Drug Administration that removes Alzheimer’s hallmark plaques from the brain and slows down memory loss. “I think I’ll have more days of happiness,” Chayrez says.

It is a measure of how bleak the outlook for patients was that lecanemab garnered so much attention — and hope. It isn’t a miracle drug. It doesn’t stop, reverse or cure this mind-robbing disorder; on average, it can slow mental decline by a mere five months over an 18-month treatment period, the research says.

It comes with dangers of its own, including the risk of brain swelling and bleeding. Studies are ongoing. But despite all these drawbacks, it represents a huge breakthrough, a foundation on which the medical community can finally begin to build.

Neurologist and Alzheimer’s researcher Randall Bateman, M.D., puts it this way: “This is the beginning of the ability to treat, and change the course of, Alzheimer’s disease.”

The first little victory

Only patients with early-stage symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease and confirmed high levels of amyloid proteins in the brain are candidates for lecanemab. In a 2023 community-based Mayo Clinic study, only 8 to 17 percent of those were eligible based on the trial criteria. And its costs — an estimated $6,636 annually, even with Medicare coverage — are prohibitive for many.

Yet after more than 40 years of studies, tens of billions in research funding, at least 146 failed drugs and plenty of public controversy and private despair among scientists, the approval of lecanemab marks a major turning point in the fight against Alzheimer’s. It’s the first “disease-modifying” drug for Alzheimer’s to receive traditional FDA approval and win standard Medicare coverage. Most significantly, lecanemab is one in a handful of recent advances expected to — at last — transform how the medical community diagnoses, treats and eventually prevents one of America’s most-feared diseases.

“I’ve been doing this for 45 years,” says geriatrician and neuroscientist Howard Fillit, M.D., cofounder and chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. “This really is a watershed time.”

Over the next five years, scientists anticipate more breakthroughs: convenient blood tests to diagnose Alzheimer’s in your doctor’s office; a variety of drugs that can attack the disease on many different fronts; and customized, research-proven lifestyle strategies that will likely become standards of care.

Within 10 years, scientists say, Alzheimer’s may be handled in your doctor’s office the way heart disease and diabetes are now — diagnosed via blood tests and treated with a combination of drugs and lifestyle strategies. The dream of patients, doctors, researchers and society: Instead of a terminal disease, Alzheimer’s could become treatable, preventable — and even reversible.

No time to waste

It’s a race against time. By 2030, 8.5 million older Americans are projected to have Alzheimer’s. A half-million of us will develop it this year.

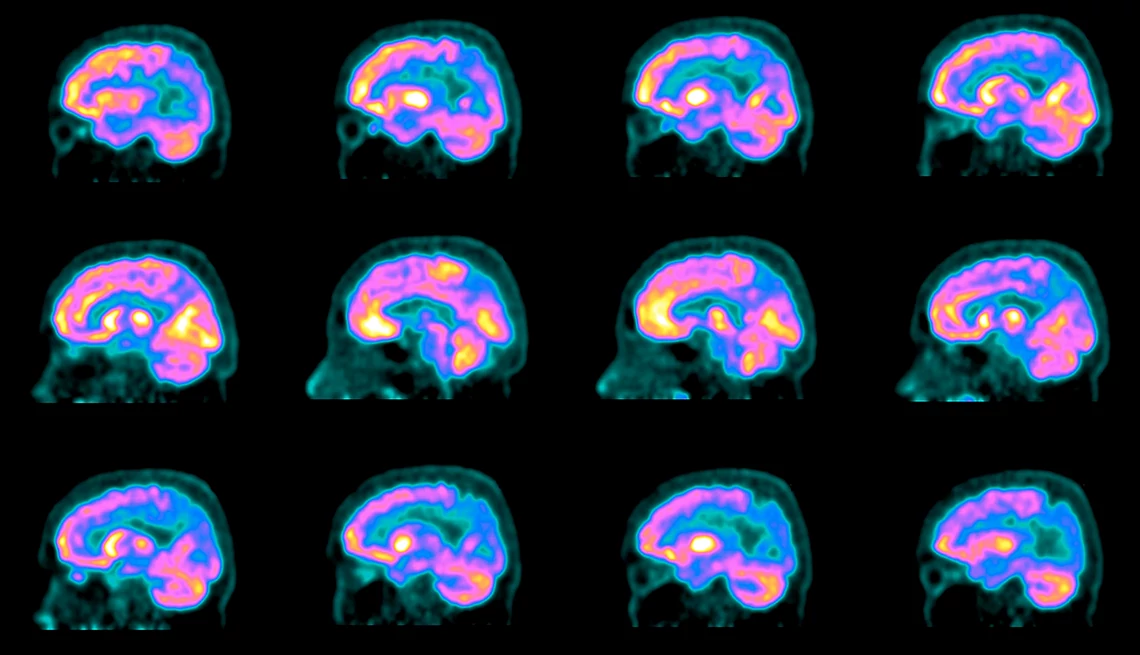

Once it begins, there’s no way to halt it. As brain cells die, connections between them wither and the brain itself shrinks, memory worsens, thinking skills decline and navigating everyday life becomes less and less possible. At least a third of people with early-stage Alzheimer’s slip into a more severe stage in about three years, putting lecanemab and possibly other early-stage treatments out of reach. Because heredity plays a role, many of us with a family history of Alzheimer’s have long looked to the future with dread.

Rochelle Long, 67, of Shaker Heights, Ohio, cares for her 86-year-old mother with advanced Alzheimer’s while working full-time. Her father, grandmother, four aunts and an uncle all had the disorder. So far, she’s OK, but optimism comes hard. “Drug companies have spent how many billions of dollars through the years, and this is where we are?” Long says. “It’s disheartening.”

Even the most optimistic experts agree that lecanemab itself won’t turn the tide — but it could become part of an arsenal that can. “For the first time, we can bend the curve of cognitive decline,” says Harvard Medical School neurologist Reisa Sperling, M.D., director of the Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Sperling is heading a new study looking at lecanemab to prevent Alzheimer’s in people at risk.

“As a neurologist who takes care of patients and someone whose father and grandfather died of the disease, I think an extra five to six months of relative stability and independence is worth it,” she says. “But it’s not good enough. We need a home run.”

And at last, the medical community may be getting its turn at bat.

More on Brain Health

Brain Health Resource Center

Tips, tools and explainers on brain health from AARPThe Six Pillars of Brain Health

Visit AARP® Staying Sharp® to learn more about the six pillars of brain health

How Does Excess Weight Affect Your Brain?

Those extra pounds can impact your brain health

Recommended for You