Staying Fit

For decades, older adults have been the backbone of American elections, consistently voting in greater numbers than any other age group. And by all appearances, older Americans were on track to be the top influencers again this November.

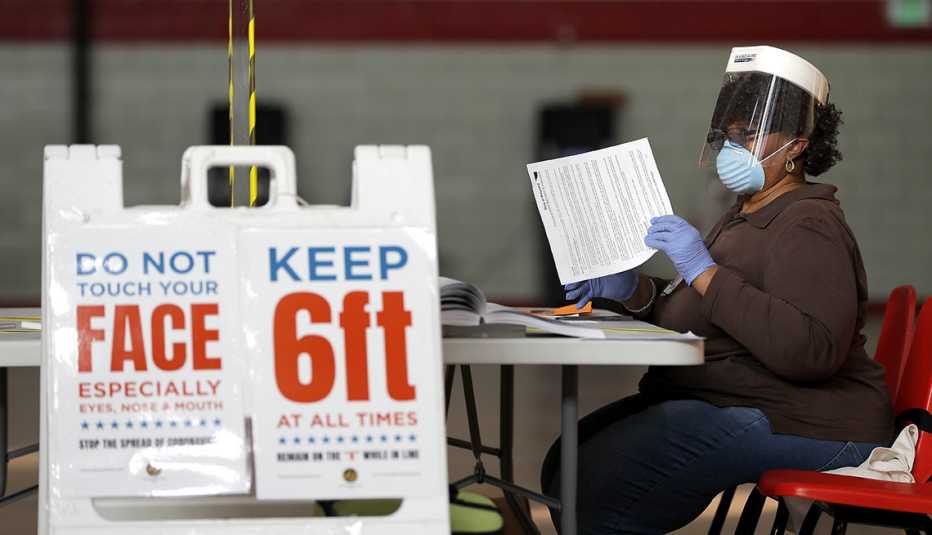

Then came COVID-19. Long lines at polling places in some of the early primaries and caucuses gave way — after the pandemic was declared on March 11 — to increased absentee balloting, tense in-person voting featuring face masks and National Guardsmen, and postponed primaries.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

The pandemic has had a cataclysmic effect on Americans’ health, jobs, wealth and lifestyles. Will it also disrupt the most fundamental responsibility of citizens: voting?

How older voters choose

In March, AARP asked over-50 voters what one thing matters most when voting for a candidate. Their answers:

"We will vote,” says Patricia Zaido, cochair of the Salem for All Ages initiative and a retired college educator in Salem, Massachusetts. “There is no doubt in my mind that we will vote.'’

Zaido, who is 80, remembers her grandfather, who immigrated to the United States from Ireland, taking her to the polling place as a little girl. “He instilled in me the importance of voting. So I guess it's in my blood."

Voter resolve

Some political experts believe that most older voters would echo Zaido's sentiments. While the way we vote might change, they say that turnout will continue to be strong and Americans age 50-plus will maintain their position as powerful decision-makers. Others caution that the pandemic could dampen turnout, depending in large part on the breadth and expanse of new coronavirus infections this fall.

Charles Stewart III, a political science professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, believes that the ongoing drumbeat of news conferences by politicians on both sides of the aisle — from the White House to governors nationwide to even some mayors — will bring home to voters how their elected officials affect their daily lives and may even boost what was already going to be a high turnout in November.

"I certainly think potential voters or voters are recognizing that it's important who their leaders are,” Stewart said.

Not that many people need extra motivation to vote this November. “This is an extremely important election, and people on both sides have strong feelings,” says Glen Bolger, a partner at Public Opinion Strategies, a Republican polling firm. “I think that older voters are going to find a way to register their opinions, whether or not it's in person."

More on politics-society

What Impact Will the Election Have on Prescription Drug Prices?

The topic remains a major issue despite the coronavirus pandemic2020 Election May Decide Future of Medicare

Growing federal deficit could force changes to the popular federal programWhat Will Happen to Medicaid After the Election?

Politicians elected to serve in the White House, Congress and statehouses will shape the future of the program