Staying Fit

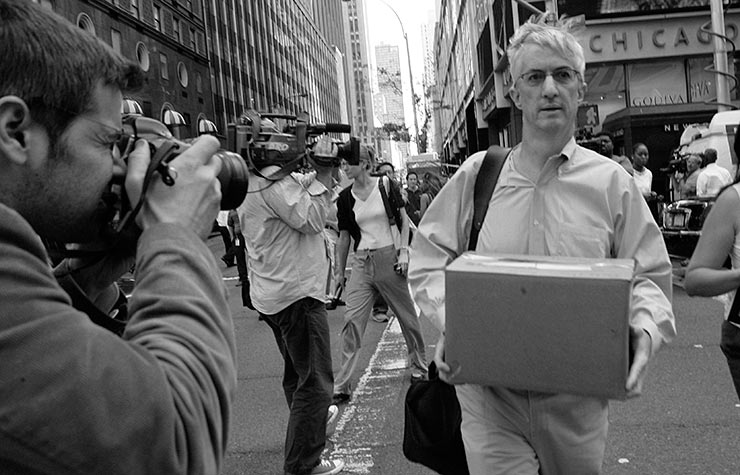

The Great Recession officially lasted from December 2007 to June 2009, but it sure seemed longer.

The economy cratered, crushing the real estate and stock markets, destroying $18.9 trillion of household wealth and wiping out more than 8 million jobs.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Sign up for the AARP Money Newsletter

But we endured — and like those who suffered through the Great Depression, we absorbed some truths about personal finance in the process. Now that the economic picture is brightening, we need to make sure we don't forget the hard lessons we learned. Below are six of the most important.

1. Just because you can qualify to borrow money doesn't mean you should

The Great Recession was triggered by the collapse of an enormous credit bubble — a bubble fueled by institutions so eager to lend that they lowered their standards to qualify more borrowers.

Banks made money selling loans to Wall Street — and Wall Street made money by packaging the loans into asset-backed securities and selling them to investors. To feed this lucrative pipeline, mortgage lenders aggressively marketed high-risk subprime loans, with little regard for borrowers' ability to repay them.

Contrary to later claims, these loans weren't made mainly to low-income, minority borrowers; by 2007, 61 percent of the subprime loans packaged by Wall Street were to borrowers with good credit scores. A comprehensive analysis of more than $2.5 trillion in subprime loans found that as the housing boom peaked, the mortgage bonanza reached every racial and ethnic group, income level and geographic area.

Then the bubble burst. Between 2007 and 2010, the median value of Americans' stake in their homes fell 42 percent; and by May 2012, 31.4 percent of homeowners with mortgages owed more than their houses were worth. And the prerecession borrowing binge wasn't limited to homeowners. Consumers, car buyers and students also took advantage of easy credit.

But debt is a huge handicap in a prolonged economic downturn. Today's low rates have tempted many Americans to refinance and extend their mortgages before they retire. That's not a good idea, says Eleanor Blayney, a certified financial planner and consumer advocate for the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards. "Those monthly payments can lock you into a lifestyle you can't adjust in bad times — and if you retire today at 65, history shows you're likely to live through two or three more economic downturns."

2. A house is primarily a place to live

If you saw yours as an ATM during the housing boom, you certainly weren't alone.

People with good credit scores opted to refinance with subprime loans in order to take more cash out of their houses than a conventional mortgage would permit. A lot of boomers also counted on their homes to pay for their kids' college.

True, subprime mortgages carried much higher interest rates — but not right away. Many had low "teaser" rates or required no initial payments at all. Borrowers figured they'd refinance again before the monthly payments skyrocketed, and might even eventually sell the house at a profit big enough to pay for their retirement.

More on money

5 Ways to Make Money by Cleaning Out Your Closet

Streamlining your clothing clutter really can be good for your wallet.

Wasted money on a purchase? Here's a look at items people buy and wish they didn't.