Staying Fit

Q: What was your path to becoming a pioneer of the internet?

I got introduced to a computer for the first time in 1958. It was taking radar signals coming from the northern part of Canada and was used to figure out whether Canadian geese were coming over the border or Russian bombers. And a couple years later I started programming. I had played the cello up until that point, and I had been taken at age 15 to a master’s class by Pablo Casals at Berkeley, and, you know, it was one of those eye-opening moments. How could any human being produce this kind of sound? But I got to the point where I was juggling cello lessons and programming computers. And programming computers was so fascinating. You create your own little universe, and then it does what you tell it to do.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

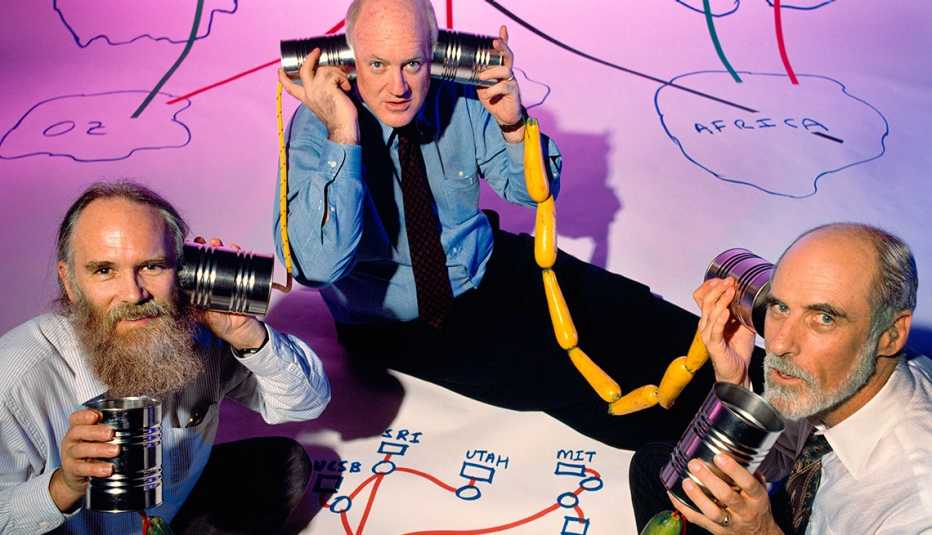

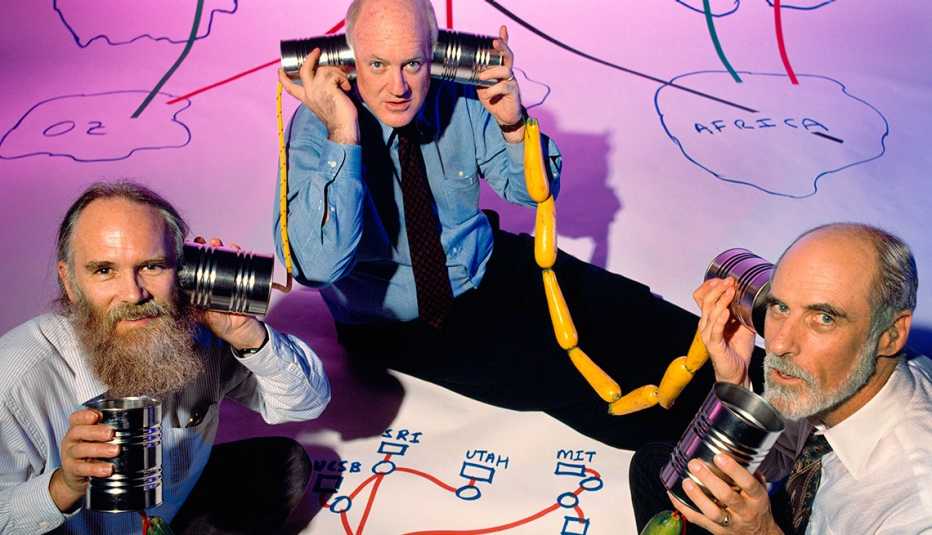

Q: Tell us about your role in the invention of the internet.

A: [Electrical engineer] Bob Kahn and I did the design in 1973. We worked for about six months to figure out how do you connect a whole bunch of different computer networks together and make it look like one net. We published a paper in 1974, and then we started implementing it.

Q: What is your biggest regret when you consider how the internet has changed our lives?

The people who were building it were a bunch of engineers — pretty much a homogenous bunch of geeks, and all we wanted was to get it to work. The general public has a rather broad range of characteristics; some people do not have other people’s interests at heart, and so they run scams and generate malware and do all kinds of things that are harmful. I’m unhappy that the internet is host to that. But it’s like every infrastructure. It’s like the road system we depend heavily on, but people get drunk, and they drive, and they destroy property or kill themselves or other people. And we don’t look to get rid of cars. So we just have to learn to make the system more secure, make you and me safer in our use of the net.

Q: Are you concerned at all that the internet isolates people, forces them into self-selected bubbles?

We do the same thing with which books we read, which movies we watch. I’ve discovered that searching the internet doesn’t necessarily get you only to the thing that you were looking for. Maybe this is like wandering around the stacks in the library and pulling the book next to the one you were looking for, and discovering there was something interesting there. This is part of critical thinking. We really have to accept the responsibility in this online environment to think critically about what we are seeing and hearing, and deliberately pay attention to the other side of the argument.

More on Home and Family

VA Caregiver Benefit Moving to Direct Deposit Only

Deadline to enroll is Oct. 1, before the VA stops sending paper checks

Free Resources to Aid Veterans, Military, Their Families Amid COVID-19 Outbreak

Check out where you can find support for your health and finances